I first heard of Monty Python’s Life of Brian when I was in high school. I was talking with a friend about Christianity and he mentioned the film: “It’s about a Jewish guy named Brian who was born the same day as Jesus. He was just an ordinary guy, but people thought he was the Messiah. It was just a big mistake. What if the same thing happened with Jesus?”

“Who was Jesus, really?”

The answer that inspired the Life of Brian goes something like this:

“Jesus was a wandering preacher. He taught about wisdom and loving others. Then, his followers tried to make him into something more. Because they were weak-minded, they felt they needed a savior from God who would solve all their problems.”

At a key moment in the film, Brian shouts to an overzealous crowd outside his widow, “You don’t need to follow me. You don’t need to follow anybody. You’ve got to think for yourselves. You’re all individuals!” And they shout back, in drone-like unison, “Yes, we’re all individuals!”

But, it doesn’t matter what Brian says. They cling to the smallest coincidences as signs and miracles. They latch on like teenage groupies and worship him as God.

The implication is plain: we’ve done the same to Jesus: we took “historical Jesus,” a completely ordinary guy, and made him into something more marketable, “The Christ of Faith.”

Does this argument hold up when we look at the historical evidence?

The Python troupe might tell us: “Come off it [in your best John Cleese accent]—ancient people told many myths about gods coming down to earth and other such rubbish. These stories are where Christians got the idea that Jesus was God.”

Besides, by the time of Jesus, Greek Mythology had gone out of fashion as the ruling common sense of the day. It was displaced by the set of beliefs historians call Platonism.

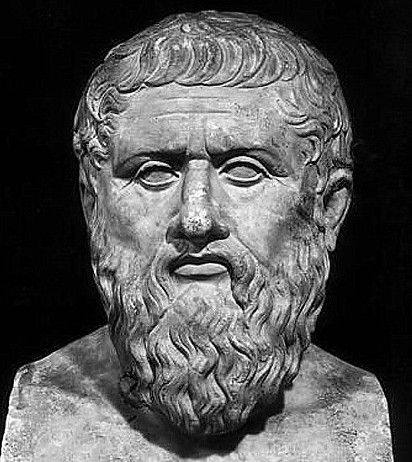

Plato, who lived about four centuries before Jesus, said the myths shouldn’t be taken at face value. Taken literary, these gods are too much like humans. Plato wanted to give the world a better image of God. He believed there had to be something above it all. Something truly Good, True, and Beautiful above the world’s suffering. Sometimes he and his disciples called it the Logos—impersonal, divine reason. This was the higher reality that ordered the chaotic lower reality. We shouldn’t think of it like Zeus—a someone we might fear or worship—but rather, a something with which we might get in tune.

So, if there were no chance in Hades that the Greeks would make up a story about the Logos becoming flesh, what about the Jews? Jesus was born into a Jewish community, after all. His first followers were Jews. Wouldn’t they be hankering to make a God-man out of some well-spoken teacher, whether Jesus or Brian or some other?

The Jewish understanding of God drawn from the Old Testament was both similar to and different than the Greeks. Like the Greek Myths, Jews believed their God was personal—a relating being, someone to fear, love, and trust. Like the Platonists, Jews believed their God was above-it-all. Jews believed there were two kinds of reality: Creator and creation, and the gap between the two was infinite. For the Jew, the God of Abraham was unpredictable, yet reliable; knowable, yet utterly mysterious.

Psalm 33:5 says, “By the Word of the Lord the heavens were made.”

In the Greek translation of the Old Testament, it says, “By the Logos of God …”

Another attribute of God that was commonly personified was Wisdom, as in Proverbs 24:30 “I [Wisdom] was beside [God], like a master workman.” These hints about a plurality in God led a Jew named Philo, who was born a few decades before Jesus, to speak of a three-in-oneness of God. He illustrated this with Genesis 18, when Abraham met three mysterious travelers. Philo thought the three represented God with his “creative power” and his “royal power” (Philo, On Abraham, XXIV, 121).

Nevertheless, Jews at the time of Jesus were radically monotheistic. There was only one God. The Creator was on the one side of reality; creation was on the other, with nothing in between. If the Logos or Wisdom of God were thought of as agents of God, they must be understood as part of the mystery that is God. A Jew in Jesus’ day could worship the one true God, yet still think there might be an incomprehensible plurality in God.

But, for the Jew, it was unthinkable that God or the Logos of God would become a human being.

However, this is what the New Testament claims about Jesus. He is “the Word (Logos) made flesh” (John 1:14). “We preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the Power of God and the Wisdom of God” (1 Corinthians 1:23–24).

Where did this idea come from?

It wouldn’t grow naturally in the soil of Greek Mythology or Philosophy. It couldn’t take off under the normal wind conditions of Jewish theology. So, what’s a plausible historical explanation for this claim that the personal Word of God became a human being and lived among us?

It must be Jesus himself.

A group of Jews spent three years with this man. They heard him forgive sins, something reserved for “God alone” (Mark 2:7). They saw him heal the lame and raise the dead, not by asking God for a miracle like the prophets, but by speaking for God personally. They were with him in the boat when he told the storm to be quiet. They said to each other,

“Who is this, then, that the wind and sea obey him?” (Mark 4:41).

The belief was not born of their felt needs for a savior. It was contrary to them. For God’s eternal Word to become flesh meant that he could suffer—get hungry and tired, be spat on and mocked, held down and crucified. This is impossible! And yet, this is what God in Jesus did.

No one would have made this up.

They did, however, come to believe it because they saw him who was crucified bodily raised from the dead.

The theoretical impossibility of the incarnation is further illustrated in the history of the early church. It took about 400 years for the Church to settle on technical language to describe what the New Testament claimed about Jesus—that he, even before he was born of Mary, was always the personal, eternal Logos of God by whom all things were made. And in the incarnation, he took human nature into his divine personhood. Now he has two natures—divine and human. These natures are united in one person without division or separation. At the same time, each of his natures remains what it is without divine nature confused with the human, nor with the human mixed into the divine.

This isn’t a story of close-minded drones believing whatever they wanted to believe. It’s a story of critical thinking disciples whose minds had been blown open to the previously unthinkable possibility that God’s personal Word, for us and for our salvation, was incarnate by the Holy Spirit and made man.

Acknowledgments

I’ve drawn most of this argument from the historical study by Oskar Skarsaune, Incarnation: Myth or Fact?